(source: this Twitter threadfrom Feb 2022)

- Ethanol is more efficient than gasoline when burned. For gasoline, we have to import it, which has environmental costs this study largely ignored.

- The biggest cost of ethanol production comes from land use: if we turn a forest into a corn field, we're netting less carbon capture, that's a new "expense" that can take ~150 years to recover from. If we take a prairie, that number is much smaller.

- We are also getting better at converting corn to ethanol, and getting energy from it.

- A forest is better than a corn field in terms of carbon capture. Ethanol is better than gasoline.

- It really comes down to your time scale: if you wait long enough (40 years), the corn CAN surpass even the forest.

Earlier this month, a study was released claiming that Ethanol is as much as 24% worse for the environment than gasoline.

First, I want to be clear: their claim is not "burning one gallon of ethanol is 24% worse than burning one gallon of gasoline". The bulk of the claim is about land use and processing. They're saying that the infrastructure to MAKE the ethanol is where the problems lie.

Their argument is actually even more complex: They aren't just talking greenhouse gasses, but surface water, soil quality, the entire ecosystem. On one hand, it's fair to look at the whole picture. On the other, it makes verifying claims difficult, and moving the goal posts easy.

For example, if making fuel out of Martian Glowcrop caused 10% fewer greenhouse gasses, but made the water 8% worse, is that a net win? It's hard to say. Real life rarely distills into easily measurable variables.

But I'm going to do my best to address the claim Reuters made: is Ethanol 24% worse per gallon than gasoline? I won't clickbait you: my answer is, broadly, no. But there's nuance. (Also to be clear: ethanol can refer to fuel made from a variety of plant material. Unless otherwise specified, I'm talking about corn here)

Subsidies

First: let's talk subsidies. The American Government subsidizes Ethanol. For every gallon of ethanol a fuel blender mixes with gasoline, they get 45¢ (formerly 51¢). This adds up to almost $6 billion a year.

There's reasons why we do this: we can grow corn here, whereas oil mostly comes from overseas. Oil is limited, corn is renewable. By diluting the gas, we extend the supply. If we cut gasoline with 10% ethanol, we're 10% less reliant on non-renewables.

But most engines aren't built for corn. It may be cheaper, but you have to buy it more often. And it makes the price of corn go up.

Disclosure

I should mention, I don't have ties to Big Corn, but I am from Iowa. Corn is the state's biggest export (followed by tractors!). The price of corn right now is $6.47 a bushel. Generally speaking, that's pretty high. Here's a chart of the last 5 years.

Corn and soybeans have BEEN high since 2006. The trend hasn't stopped. I'll come back to this later, but part of the reason for it is because demand for corn has gone up. Much of the corn is being converted to ethanol.

The government is paying for ethanol (and corn) via subsidies, so farmers want more land to make corn. So let's talk about subsidies.

Subsidies and Land-Rent

The government pays farmers to plant certain crops. These subsidies influence land use. If the government is paying for corn, that changes the market. If corn makes money, corn gets planted.

It means less diversity in your farms, and it means farmers aren't necessarily doing what's best long-term.

Farming takes a TON of ag-science, and subsidies answer a different question. Not "What does the land need" or "What's good for the market", but "What does the nation want", and that's what gets grown. ...At least, that's what some detractors would have you believe.

The US government subsidizes only 5 crops: soybeans, cotton, rice, wheat, and, of course, corn. But they also pay farmers NOT to grow crops! Usually this is done for enviro reasons (it's bad for land to be planted with the same crop year in and year out. See Ag Science, above).

In fact, last year the Biden administration increased the amount of land-rent, in an effort to reduce agricultural runoff and reduce greenhouse gasses.

The way it works is the government says "hey, don't plant anything here, and we'll pretend you planted whatever you've been planting there, and "buy" it off you anyway.

(I've proposed elsewhere a similar scheme for decreasing the US's economic dependence on our own bloated defense budget)

We can talk about the ethanol subsidy and whether it's even necessary (other legislation mandates certain production of biofuels INCLUDING ethanol, which makes the subsidy a bit of a carrot when some would argue that the stick is sufficient).

We could talk about how when Trump wanted to reduce the subsidy, the Midwest revolted, even faithfuls like Iowa senators Grassley and Ernst.

But that's a little off topic, and I assume your interest in corn is limited. I'll just say this: if you think the ethanol subsidy is going away, I'll remind you that the current secretary of agriculture previously served as the governor of Iowa (until 2008).

Back to the Study

The study's first claim is that the amount of ethanol created has been rising. That's true. As discussed, legislation REQUIRES a certain percent of all fuels be biofuel. The US grows a ton of corn, so it's ethanol that gets made. It's (relatively) cheap.

There's more ethanol now, but there's also just more PEOPLE. The best guess is that 32% of the increase from '06-'09 was due to ethanol.

There's another reason this study is coming up now, and it's an important one: that legislation that requires fuel be biofuel? The blending requirement only extends through 2022.

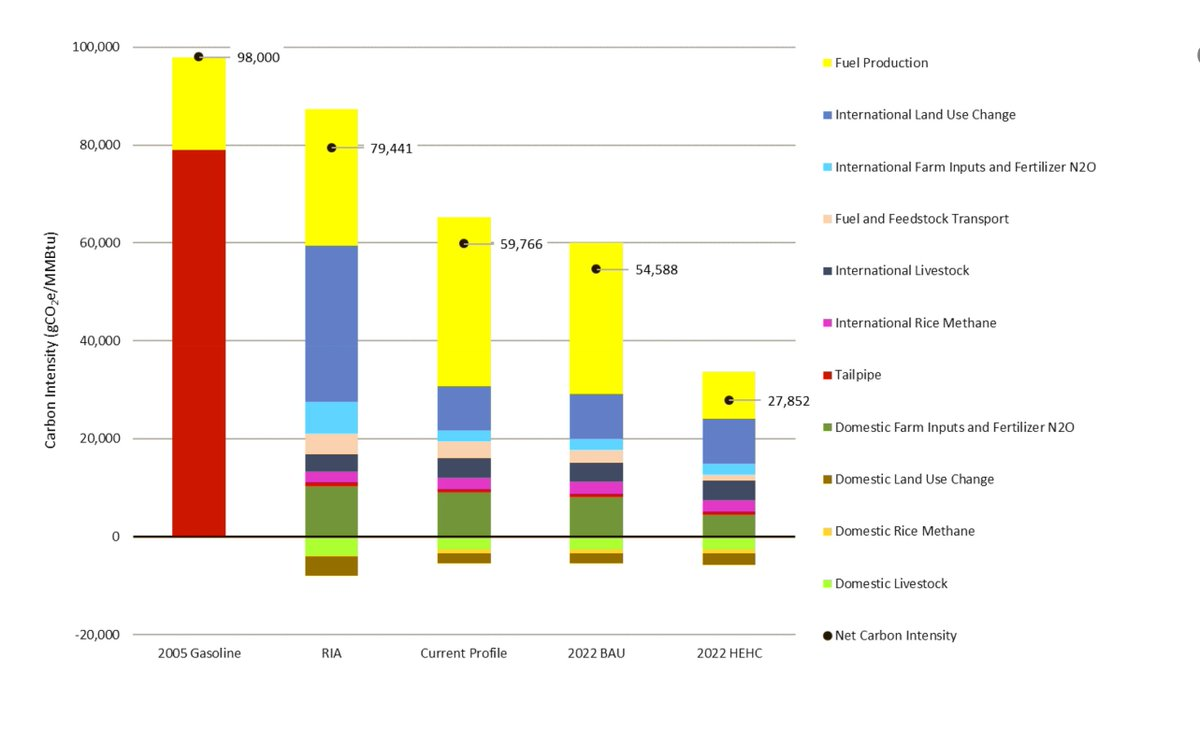

It's critical to note that ethanol DOES produce fewer greenhouse gasses than gasoline. In fact, it MUST: in order to qualify as a biofuel, it must produce at least 20% fewer emissions than gasoline did in 2005. But as I stated earlier, that's not the claim being made.

Aside, credits

After the 2022 blending credits expired, congress suggested a new proposal to increase blending requirements even more in 2023 and the years following.

But it turns out there's two ways to make compliance. By blending, or by buying credits.

Buying credits is generally rather silly. You pay someone else who promises to make less carbon and in exchange you get to make more. It's a shell game, and extremely common in all eco-fields. It's where much of Tesla's revenue comes from.

One gallon of ethanol gives you one credit (called a RIN ("Renewable Identification Number"). But there's a problem: "These refiners have reported paying more for RINs than all of their other operational costs combined, including payroll, utilities, and maintenance," !

The price of credits increased 1200% (!) from 2020-2022. Which means it's not longer profitable to buy credits. So refineries have a choice: stop being compliant, or start actually blending. Naturally, they push for lower blending requirements so they can keep as usual.

Land use

This month's study (Study A) frequently cites an earlier study from 2008 (Study B, source #10 in my refs). One of the biggest concerns from Study B was re: farmers taking new land & converting it to corn. Depending on the kind of land they use, this ranges from bad to disastrous.

The argument goes like this: growing corn reduces CO2. It's a plant. But when land is growing corn, it's not growing anything else. Corn is less good at pulling CO2 than other things.

So Farmers destroy forests and grasslands to get at those subsides we talked about earlier. Also, a corn that's being burned is WORSE than a tree that isn't.

The argument continues: if the land was something carbon-worse than corn (like prairie), we may be okay. But in the worst case, we're chopping down forests, and things get real bad.

Study B assumes that all of the land being converted to corn is carbon-better than corn. In other words, that any farmer turning any land to cornland is doing a disservice.

They generated a computer model (that the authors are rather vague on) to see what the world would look like in 2022 if the farmers start claiming land. And again, they assumed that the land was largely forest.

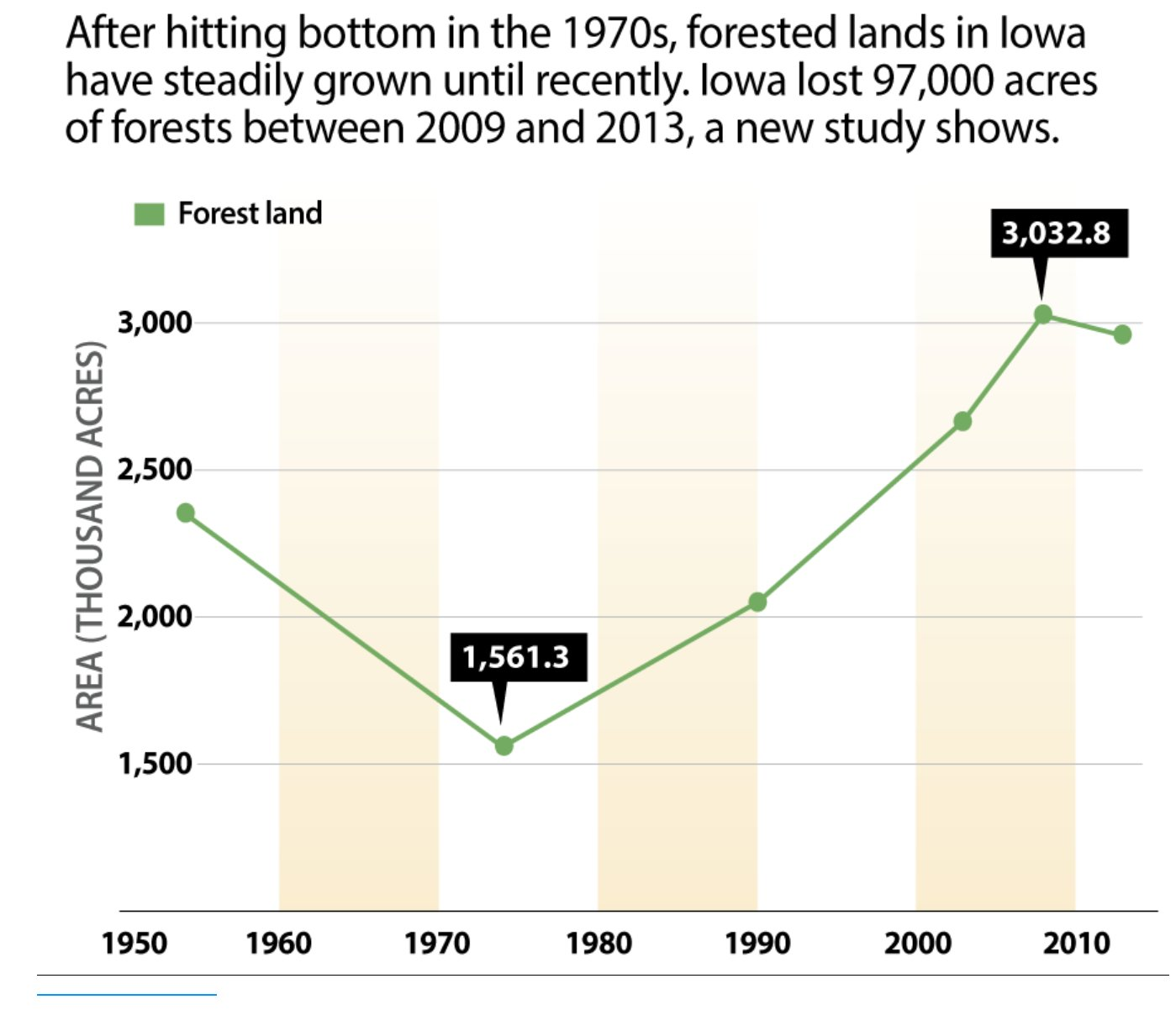

The study's base assumption is that farmers are chopping down forests and plowing savannah to make ethanol. That's somewhat true! Between 2009 and 2013, Iowa lost 97,000 acres of forest. And 71% of that came from agriculture! (Des Moines Register)

There are similar trends across the country.

Corn expanded into almost 7 million more acres between 2008 and 2016. And that land had to come from somewhere. ...But 91% of it comes from pasture, with only 3.3% coming from forests. And that 7 million acres is smaller than what the study predicted.

Farmers are smart. They didn't take new land, but fallow fields and shrinking temporary pasture. They used techniques like double cropping to increase corn production. So the bogeyman of land-use change didn't appear. Good news!

What about the rest of the model's predictions?

But we can't blame a computer model for getting some things wrong, the general idea could be sound. Let's keep going. Even though I don't know the details of the model, they make do some strong claims:

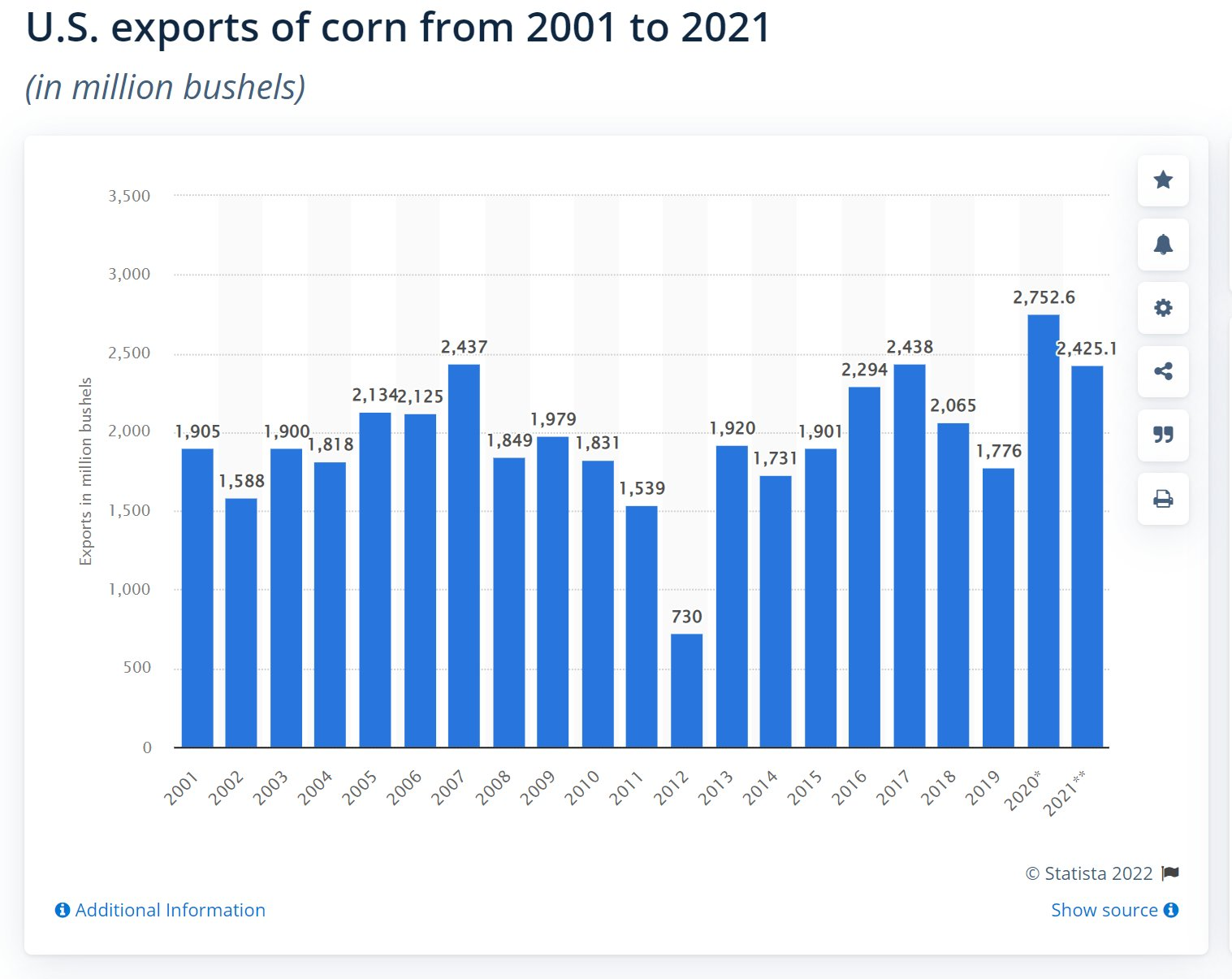

As cropland switches to ethanol, they expect corn exports to drop 62% (!) that's huge! but it's been more than a decade since this was published, that seems easy to track.

Hmm. The first thing you'll notice is 2012. There was a huge drought that year, let's ignore it. Aside from the drought year, corn exports have not decreased since this article was written.

That's not a complete debunkment: They hedge and say 62% compared to what they otherwise might have been. I'm no economist, so maybe they expected a dramatic increase in exports, and what we see IS a 62% decrease. But my gut says that this kind of growth is NOT a 62% decrease.

In fact, I can go further: they make one claim that's easily falsifiable: that other countries will replace the US as exporters. Since 2016, the US is the world's largest exporter of corn.

We're also the second (or third, depending on how you measure) largest exporter of wheat, and #2 for soybeans. Now it is worth noting that sometime around 2010 Brazil passed the US in soybean exports. 1 point in the study's favor.

On to their next point: it's not that ethanol is expensive to burn, but that it's expensive to process. Making ethanol looks something like this: Photosynthesis makes sugars -> fermentation of those sugars -> combustion to energy! But there's refineries involved.

Between the land-use (mostly debunked above) and the processes in general, it can take up to 167 YEARS for newly claimed land to be efficient enough to offset the plants that were destroyed to make it into cornland.

Wow! There's a lot of guesswork in the study, and even they admit that some of their figures are hard to track. I don't know how accurate their numbers are, but the method seems sound. But there's one damning flaw:

Efficiency

They're predicting ethanol that, compared to gasoline, creates 20% fewer greenhouse gasses. Maybe that was true in 2008, but today that number is almost double, to 39%. This takes the devastating 167-year equilibrium down to 85 years. Still not great. But wait!

They accounted for this, using a 40% as a best-case scenario (along with some other optimistic increases in farming tech (once again, ag science for the win!). With these changes, they get down to 37 years before a payoff.

I don't know enough about the realism of the other changes they modeled, but they nailed this one, so I'll give the authors credit. 37 years isn't ideal, but it's at least measurable. That's within a human lifespan. Or it would be.

This number uses 30 billion liters per year, while actual usage is closer to 60 billion. Back to 75 years.

Brazil

So the argument seems to stand: conversion of land to ethanol production outweighs the benefit. But hope isn't lost! Sugarcane ethanol can be as much as 90% more efficient than gasoline! We don't grow that in the US, but Brazil does!

..which brings us back to land use. If Brazil turns grazing land to sugarcane, we're looking at 4 years to neutral. If they convert rainforests? 45 years! Let's leave the rainforests alone!

Unsurprisingly, Brazil has the most successful biofuel programs in the world. Their sugarcane produces 8-9 times more energy than it takes to process it. The US leads biofuel production by volume, Brazil by effectiveness. No one else comes close.

Solutions

So what can the US do? Remember those subsidies for unused croplands? Revert them back fully. Turn them into forest or grassland. Capture that carbon. The ethanol isn't worth it.

I want to be clear: I'm not saying ethanol is bad. I'm saying that converting good cropland to make more biofuel is a net negative.

So that seems like a nail in the coffin of corn ethanol, right? Not so!

Improvements to the production pipeline

Study A makes another claim of their own: It's not the burning of ethanol that's the problem, but the production pipeline. Study A claims that old ethanol refineries are less efficient, but are being grandfathered in.

This is a huge claim. The main source of emissions reductions with respect to ethanol is not better engines or the (considerable) lack of forested land use, it's improvements in the refinement process.

Specifically, the shift to sustainable biomass as the process fuel in refineries. Should we continue these trends, it could get 45-70% more efficient than gasoline (!)

Again, these stats are for existing cornland: even at 70% efficient, additional land use is not great: we'd be looking at about 35 years to neutral again.

There have been massive improvements to the process of ethanol refinement. ~5% of ethanol's GHG profile comes from transporting to from refinery to retail. Of course, these vehicles have been getting more efficient since 2010.

(and this ignores the comparable process of shipping oil across an ocean)

The process of refining takes fuel. In 2010, that was largely coal. Now it's natural gas. These changes make ethanol look bad a decade ago and more efficient now.

One of those ag science reductions is in reduced tillage. Compared to conventional tillage, the modern approach cuts down on soil carbon and CO2 emissions. look at how much better we're doing (right column) than the estimates (second to right column)

If there really are coal-burning refineries that are being lumped in, it's not showing up in the data. Which means the claim is either false or insignificant. Another point to ethanol.

Most (47%) Greenhouse gas emissions in ag are from livestock, which is fed with corn. Between this and the sheer amount of water it takes to raise a pound of beef, there's an excellent argument to be made for vegetarianism from the environmental point of view.

There's a whole lot of information about livestock feed as a byproduct of ethanol that I frankly don't have the ag sci background to understand. It seems like making ethanol makes it easy to feed cows, which sounds like an added plus, assuming the beef industry isn't going anywhere. This feels like a safe assumption.

Summary

To summarize: study A relied a lot on a 14-year-old study B, which made a lot of predictions about the future. Some of those predictions turned out, others did not.

As a whole, ethanol is beating most of the predictions, but the requirements (sticks) and subsidies (carrots) are up for renewal this year. It's all up to the government now

Conclusion: It takes a long time (~30 years) for land that is not currently producing corn to become net negative after converting to ethanol. Existing ethanol is getting more efficient every day. This is all a drop in the bucket compared to sugarcane.

Ethanol is better than gasoline once it's burnt, the question is in production. Existing ethanol land is probably coming out ahead. Gasoline is far away, and it is expensive to move it. Ethanol, by comparison, moves ~50 miles while processing.

Sources

1 https://thoughtco.com/understanding-the-ethanol-subsidy-3321701… 2 https://macrotrends.net/2532/corn-prices-historical-chart-data…

3 https://markets.businessinsider.com/commodities/corn-price…

4 https://tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17597269.2018.1546488…

5 https://pnas.org/content/119/9/e2101084119…

6 https://thecounter.org/biden-administration-farmers-conservation-reserve-crp-usda-vilsack/…

7 https://downsizinggovernment.org/agriculture/subsidies…

8 https://reuters.com/business/environment/us-corn-based-ethanol-worse-climate-than-gasoline-study-finds-2022-02-14/…

9 https://enotrans.org/article/pay-farmers-not-grow-crops-dont…

10 https://science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.1151861…

11 https://statista.com/statistics/191026/us-exports-of-corn-since-2001/…

12 https://investopedia.com/articles/markets-economy/090316/6-countries-produce-most-corn.asp…

13 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_wheat_exports…

14 https://statista.com/statistics/961087/global-leading-exporters-of-soybeans-export-share…

15 https://oec.world/en/profile/hs92/soybeans…

16 https://desmoinesregister.com/story/money/agriculture/2016/07/16/iowa-losing-millions-trees-and-is-hurting-water-quality/87074442/…

17 https://usda.gov/media/blog/2019/04/02/building-evidence-corn-ethanols-greenhouse-gas-profile…

18 https://statista.com/statistics/190862/area-of-corn-for-grain-harvested-in-the-us-since-2000/…

19 http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2010/ph240/luk1/…

20 https://usda.gov/media/blog/2019/04/02/building-evidence-corn-ethanols-greenhouse-gas-profile…

See Also

Decoupling the Military Industrial Complex

The Grapes of Wrath