Strong Link Vs Weak Link

Source: Science is a Strong-link problem

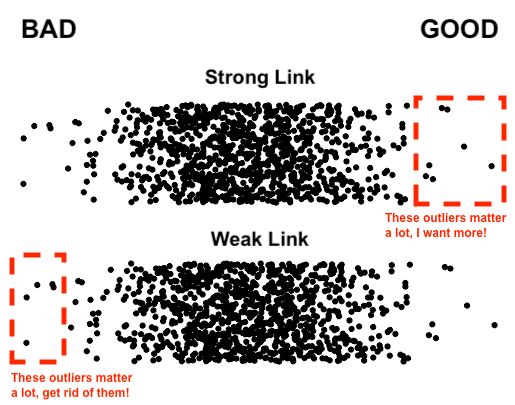

There are two kinds of problems in the world: strong-link problems and weak-link problems.

Weak-link problems are problems where the overall quality depends on how good the worst stuff is. You fix weak-link problems by making the weakest links stronger, or by eliminating them entirely.

Food safety, for example, is a weak-link problem. You don’t want to eat anything that will kill you. That’s why it makes sense for the Food and Drug Administration to inspect processing plants, to set standards, and to ban dangerous foods. The upside is that, for example, any frozen asparagus you buy can only have “10% by count of spears or pieces infested with 6 or more attached asparagus beetle eggs and/or sacs.” The downside is that you don’t get to eat the supposedly delicious casu marzu, a Sardinian cheese with live maggots inside it.

It would be a big mistake for the FDA to instead focus on making the safest foods safer, or to throw the gates wide open so that we have a marketplace filled with a mix of extremely dangerous and extremely safe foods. In a weak-link problem like this, the right move is to minimize the number of asparagus beetle egg sacs.

Weak-link problems are everywhere. A car engine is a weak-link problem: it doesn’t matter how great your spark plugs are if your transmission is busted. Nuclear proliferation is a weak-link problem: it would be great if, say, France locked up their nukes even tighter, but the real danger is some rogue nation blowing up the world. Putting on too-tight pants is a weak-link problem: they’re gonna split at the seams.

It’s easy to assume that all problems are like this, but they’re not. Some problems are strong-link problems: overall quality depends on how good the best stuff is, and the bad stuff barely matters. Like music, for instance. You listen to the stuff you like the most and ignore the rest. When your favorite band releases a new album, you go “yippee!” When a band you’ve never heard of and wouldn’t like anyway releases a new album, you go…nothing at all, you don’t even know it’s happened. At worst, bad music makes it a little harder for you to find good music, or it annoys you by being played on the radio in the grocery store while you’re trying to buy your beetle-free asparagus.

Because music is a strong-link problem, it would be a big mistake to have an FDA for music. Imagine if you could only upload a song to Spotify after you got a degree in musicology, or memorized all the sharps in the key of A-sharp minor, or demonstrated competence with the oboe. Imagine if government inspectors showed up at music studios to ensure that no one was playing out of tune. You’d wipe out most of the great stuff and replace it with a bunch of music that checks all the boxes but doesn’t stir your soul, and gosh darn it, souls must be stirred.

Strong-link problems are everywhere; they’re just harder to spot. Winning the Olympics is a strong-link problem: all that matters is how good your country’s best athletes are. Friendships are a strong-link problem: you wouldn’t trade your ride-or-dies for better acquaintances. Venture capital is a strong-link problem: it’s fine to invest in a bunch of startups that go bust as long as one of them goes to a billion.

Figuring out whether a problem is strong-link or weak-link is important because the way you solve them is totally different:

When you’re looking to find a doctor for a routine procedure, you’re in a weak-link problem. It would be great to find the best doctor on the planet, of course, but an average doctor is fine—you just want to avoid someone who’s going to prescribe you snake oil or botch your wart removal. For you, it’s great to live in a world where doctors have to get medical degrees and maintain their licenses, and where drugs are thoroughly checked for side effects.

But if you’re diagnosed with a terminal disease, you’re suddenly in a strong-link problem. An average doctor won’t cut it for you anymore, because average means you die. You need a miracle, and you’re furious at anyone who would stop that from happening: the government for banning drugs that might help you, doctors who refuse to do risky treatments, and a medical establishment that’s more worried about preventing quacks than allowing the best healers to do as they please.

Slack

A Fred Sanger would not survive today's world of science. With continuous reporting and appraisals, some committee would note that he published little of import between insulin in 1952 and his first paper on RNA sequencing in 1967 with another long gap until DNA sequencing in 1977. He would be labeled as unproductive, and his modest personal support would be denied. We no longer have a culture that allows individuals to embark on long-term—and what would be considered today extremely risky—projects.